EIPs For Nerds #3: EIP-7251 (Increase MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE)

Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away. — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

I often talk about rational optimism—I wrote an entire article about the intersection between rational optimism and crypto at the height of 2022’s bear market—and like to identify as a “rational optimist”. But there are many downsides to rational optimism that people like Naval Ravikant and Andreessen Horowitz won’t tell you.

Being a rational optimist isn’t just about working to solve problems; it also involves (a) acknowledging you might create new problems—which will only show up later—in the process of solving an existing problem, and (b) dealing with the despair that comes from seeing how your previous problem-solving actions led to another problem in the present. As a TED Talk once put it, the art of progress is essentially creating new problems to solve:

“Progress does not mean that everything becomes better for everyone everywhere all the time. That would be a miracle, and progress is not a miracle but problem-solving. Problems are inevitable and solutions create new problems which have to be solved in their turn.” — Steve Pinker

This semi-philosophical introduction is vital to discussing the next Ethereum Improvement Proposal (EIP) in the EIPs for Nerds series: EIP-7251. EIP-7251 is a proposed change to Ethereum’s Proof of Stake (PoS) consensus protocol that will increase the maximum effective balance (MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE) for validators on the Beacon Chain from 32 ETH to 2048 ETH. EIP-7251 also introduces validator consolidation, which will allow large stakers to run fewer validators by consolidating balances from multiple validators into a single validator.

While EIP-7251 looks like a simple change, increasing the validator’s effective balance is one of the most significant changes to the core protocol—possibly right up with enabling withdrawals—since The Merge. This article provides a rough overview of EIP-7251, including the advantages and potential drawbacks of implementing the EIP, and includes enough details to help make sense of the why and how of increasing MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE for validators.

Let’s dive in!

Setting the stage: A lack of serenity in Ethereum’s consensus

Ethereum’s transition Proof of Stake (fka “Ethereum 2.0”) was originally called the Serenity upgrade (I don’t know why the name “Serenity” was chosen—but many expected the Serenity upgrade to fix all of Ethereum’s problems, so the name seems fitting). Now, the Ethereum 2.0 (note that I’m using “Ethereum 2.0” for historical context only) we got isn’t quite the Ethereum 2.0 some imagined it would be (i.e., achieving Visa-like scale with execution sharding, or transitioning from the EVM to eWASM for more efficiency), but it works.

For example, solo stakers currently make up a decent percentage of the Beacon Chain’s validator set—recall that reducing the barrier to running a validator was a key goal of switching to Proof of Stake—and Ethereum PoS has remained “World War III-resistant” despite concerns around centralization of stake. There are rough spots, including something about LSDs (not the drug), but nothing enough to stop the Beacon Chain from operating as the economically secure, “green,” decentralized settlement layer it was designed to be.

All seems well with Ethereum’s consensus, but problems are hiding under the surface.

One of those problems is the negative second-order effects of having an extremely large validator set (the Beacon Chain currently has ~800,000 active validators and will likely cross the million-validator threshold in a few months).

Having many validators theoretically improves Ethereum’s decentralization, especially if you compare it to traditional Proof of Stake protocols that limit participation in consensus to 100-200 “super-validators”. But an extremely large validator set introduces problems with implications for the network’s health and long-term sustainability. Unsurprisingly, many of these problems have only become evident as the validator set on Ethereum increased in the months following The Merge and the activation of withdrawals in the Shanghai-Capella upgrade.

While Ethereum’s validator set growth was inevitable, especially with the popularity of liquid staking, the large validator set is partially a consequence of previous design decisions (“tech debt” in nerd-speak). This explains why I started with a philosophical talk on rational optimism—to show how creating solutions leads to creating complex problems that demand even more complex solutions.

The design decision in question? Limiting validator’s maximum effective balance (MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE) to 32 ETH. In the next section we’ll see what effective balance means, and explore how capping the maximum effective balance at 32 ETH contributes to the Beacon Chain’s growing validator set.

Understanding MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE in Ethereum

A validator on Ethereum has two balances: an actual balance and an effective balance. The “actual balance” is simply the sum of the validator’s initial deposit and the rewards minus any penalties and withdrawals. The effective balance is derived from the validator’s actual balance and represents “the maximum amount a validator has at risk from the protocol’s perspective.” We can further break down this definition to have a better mental model of a validator’s effective balance:

1. “The maximum amount a validator has at risk” is a reference to the core principle of Proof of Stake: economic security is a function of a protocol’s capacity to levy a high cost on actions that can be construed as an attack on the protocol—whether those actions are deliberate or accidental is irrelevant—by destroying part or all of the collateral pledged by validator before joining the protocol. An example of a protocol-violating behavior is lying about the validity of a block (each validator “votes” for a block and is expected to vote for a block if it has evidence the block includes valid transactions).

This is why PoS protocols like Ethereum’s Gasper are designed to use validator balances to inform decisions like selecting a validator to propose a new block, calculating rewards, and slashing validators that provably deviate from the protocol’s rules. The theory is that a validator with “more at stake” has less incentive to act dishonestly since the penalty for dishonest behaviors is dynamic and increases in proportion to the collateral pledged by the validator.

In the context of the Beacon Chain, a validator’s effective balance determines the validator’s weight or influence in the consensus protocol. For instance, a Beacon Chain block becomes final (i.e., irreversible) if the total stake of validators that voted for a block represents a supermajority (66% or more) of the total stake of all active validators. To understand how and where a validator’s effective balance is used in Beacon Chain consensus, I encourage reading Economic aspects of effective balance.

2. “From the protocol’s perspective” means the Beacon Chain always sees each validator as having at most 32 ETH (the maximum effective balance) staked in the protocol. Any other amount over the maximum effective balance isn’t considered “at stake” and cannot be slashed—nor does it count towards the rewards a validator earns for carrying out duties correctly—making it “ineffective” from the protocol’s perspective.

A validator’s actual balance will expectedly increase once it starts receiving rewards and doesn’t get slashed. However, the Beacon Chain conducts a “sweep” at every block and automatically withdraws amounts over 32 ETH to the execution-layer address specified in the validator’s withdrawal credentials (see EIPs For Nerds #2: EIP-7002 (Execution-Layer Triggerable Exits) for an in-depth discussion of withdrawal credentials). Not every validator receives partial rewards immediately, but most estimates suggest that a validator will receive partial rewards on a frequency of 5-7 days.

Why was MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE set to 32 ETH initially?

The value of 32 ETH as the MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE is a carryover feature from the original sharding roadmap. At the time, the vision was to split the Ethereum network into 64 sub-networks (shards), with each subnet processing sets of transactions in parallel and the Beacon Chain serving as a coordination layer for the network.

Under this arrangement:

Every active validator on the Beacon Chain was assigned to a committee designated to produce attestations for one of the 32 slots in an epoch. The committee attesting for each slot was broken into 16 subcommittees (a.k.a., Beacon committees) with a target of 64 validators and a maximum of 128 validators per subcommittee.

Each subcommittee would validate one of the 64 shards and attest to blocks from shard proposers. The shard proposer aggregated attestations from at least ⅔ of the validators in a subcommittee before broadcasting the block’s header—which included signatures of validators that attested to the block—to the Beacon Chain.

Validators in the “main” committee for the slot voted on the validity of shard blocks by checking block headers (described as “cross-links”) and confirming that a majority (⅔) of validators in the subcommittee signed the block, and those signatures corresponded to public keys of existing validators.

A concern with this sharding design was the susceptibility of a shard to attacks by a dishonest majority of validators—an adversary that controlled enough members of the committee attesting to a shard’s transactions (e.g., > ⅔) had a high probability of getting the Beacon Chain to finalize invalid shard blocks. Thus, it was necessary to ensure that:

Every validator in the protocol had equal probability of appearing in the committee for a shard. This made it difficult for an attacker to predict if the validators it controlled would end up in a particular shard committee and reduced the likelihood of a malicious takeover of one or more shards.

Validators had roughly the same weight or influence in the consensus protocol. Without this feature, an attacker still had a chance of gaining undue influence in a subcommittee, as the protocol used the total validator weight (the amount staked by each validator) that attested to a block, and not validator count (the number of validators that voted for a block), to determine if a block was eligible for finalization.

The solution for problem #1 was to design a verifiably random function (VRF) and use it as a source of randomness to inform validator assignments to committees. A visual description of the random assignment of validators is shown below:

Solving problem #2 meant limiting each validator’s effective balance—which represented its weight in the protocol—to a constant of 32 ETH. If MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE was variable, an attacker could finalize an invalid block if it controlled ⅔ of the entire stake in a committee—even if ⅔ of validators in the committee were honest. Conversely, giving every validator equal weight in the committee reduced the possibility of a minority of validators exerting outsized influence on a shard’s consensus.

You may also notice MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE is also the minimum deposit amount (32 ETH) required to activate a validator. This isn’t a coincidence. Unlike the original proposal for a minimum deposit of 1500 ETH, a lower activation balance of 32 ETH increased the likelihood of more people running Beacon Chain validators and ensured adversaries had a negligible probability of controlling ⅔ of validators in a committee. Minimum Committee Size Explained provides a formal explanation of this concept and is useful for understanding the original security design of subcommittees.

Why is a MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE of 32 ETH no longer necessary?

Subcommittees became surplus to requirement once Danksharding replaced the original sharding roadmap. More importantly, the Beacon Chain’s security property (e.g., the validity of transactions finalized by the consensus protocol) was no longer reliant on the assumption that ⅔ of validators in every subcommittee was honest.

Why the change?

In the execution sharding model, each shard was expected to run an instance of the EVM (Ethereum Virtual Machine) and process state transitions. An attacker controlling a majority of validators in the subcommittee attesting to a shard could do nasty things, like steal funds from a smart contract by finalizing invalid state transitions.

Similarly, subcommittees in the original data sharding design (before Danksharding) required a majority of validators to be honest. Otherwise, a malicious shard proposer could perform a data withholding attack—refuse to publish blobs posted to the shard—and degrade the liveness and safety of rollups that relied on Ethereum for data availability.

Danksharding has since superseded both sharding designs and replaces the multi-proposer model with a single-proposer model: there is precisely one block added to the Beacon Chain during a slot, and all validators assigned to that vote for this block. Since every subcommittee is voting on the same set of transactions, an attacker needs to control a supermajority of all active validators in the slot to mount a successful attack (e.g., finalizing an invalid block).

To clarify, validators attesting in a slot are still broken up into subcommittees; however, the only benefit to assigning validators to subcommittees is improving the efficiency of aggregating attestations on the Beacon Chain. For context, a valid block must include signatures from a quorum of validators whose stakes represent a supermajority (>= ⅔ ) of the total stake in a slot committee; assuming all validators have the same maximum effective balance of 32 ETH, a block proposer needs signatures from ⅔ of validators attesting in the slot.

Aggregators are introduced into the subcommittees, with each subcommittee having 16 aggregators, to reduce bandwidth requirements for proposers and validators:

An aggregator collects attestations (signatures) to a block from validators assigned to a subcommittee and creates an aggregate signature using the BLS signature aggregation algorithm. Aggregators from a subcommittee send aggregate attestations to the proposer, and the proposer chooses the “best” aggregate attestation (“best” meaning “the aggregate attestation with the most signatures”).

The upside: Proposers don’t have to aggregate signatures from thousands of validators assigned to a slot (the Beacon Chain has 800,000+ validators today, so every slot in a 32-slot epoch will have ~25,000 validators attesting per slot). In addition, validators in the slot committee only verify 64 aggregate signatures instead of verifying thousands of signatures on a block before finalizing the block.

We need a subcommittee to have one honest aggregator since a validator can only influence Beacon Chain consensus if its attestation is included in a block. A dishonest aggregator can manipulate the fork-choice rule by refusing to broadcast aggregate attestations to the proposer, or excluding attestations from a set of validators. However, if at least one of the 16 aggregators in a subcommittee is honest and doesn’t censor attestations, honest validators in the subcommittee can influence the Beacon Chain’s fork-choice mechanism.

The observation that subcommittees can operate with honest-minority (1-of-N) assumptions implies that setting MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE to a constant of 32 ETH is no longer necessary. We could leave the maximum effective balance untouched in the spirit of “if ain’t broke, don’t fix it”, but capping the MaxEB for validators introduces new problems exacerbated by the increasing appeal of staking on Ethereum.

Why is capping MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE at 32 ETH a problem today?

Imagine you’re running a staking service, and promise stakers eye-popping APRs on staked ETH. To hold up your end of the bargain, and profit from the arrangement, you need to earn enough rewards from validating to pay back the promised yield and cover operational costs. However, the Beacon Chain caps the maximum effective balance for each validator at 32 ETH and automatically schedules every additional wei for withdrawal; plus, even if your validator’s balance reaches 33 ETH before the withdrawals sweep activates, the extra 1 ETH is inactive and doesn’t figure into the calculation of rewards.

Fortunately, there’s a simple workaround: you can combine excess balances of multiple validators to fund a new 32 ETH validator and start earning fresh rewards. Repeating this process (earn rewards → withdraw rewards → consolidate rewards into 32 ETH → activate a new validator) at intervals compounds staking rewards and ensures compound staking rewards and ensures you can keep stakers happy, pay taxes, and remain profitable. You can even increase profits from economies of scale by running multiple validators on the same machine (a “validator” is simply a computer process identified by a public-private keypair).

On the surface, this looks like a good business model for an institutional staking service or staking pool. But it doesn’t take a genius to see the problem: a large staking pool is forced to spin up multiple validators to maximize earnings even if the same entity operates those validators. The emphasis on the last part reflects the differences between the network’s notion of a validator and the real-world notion of a validator:

The network sees each validator as a unique entity: A validator joins the entry queue after placing a deposit in the deposit contract (the

depositmessage is indexed with a unique ID); once activated, the validator sends attestations that must be processed separately from attestations sent by other validators. Also, balances for two validators cannot be merged in-protocol; both validators have to exit before their stakes are combined and used to fund a new validator. (The cumulative balances of the two validators must be lower than theMAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCEof 32 ETH for the new validator to earn rewards for every unit of ETH staked.)

In real-world scenarios, multiple validators may be funded by the same address and share the same withdrawal credentials. Additionally, messages (including attestations and voluntary exits) broadcasted on the network may originate from the same entity that controls signing keys for multiple validators. Similarly, the

depositmessage for two validators may be from the same operator who is simply consolidating rewards from existing validators to activate new validators (with all validators running on the same machine).

To illustrate, the biggest staking pool today (Lido) controls more than ~275,000 validators and has 40+ node operators. Seeing the outsized ratio of validators to node operators, it doesn’t take a genius to see that “Lido’s 275,000 validators” can be more accurately described as “Lido’s 6,875 validators” (this assumes each operator controls an equal number of validators and all validators run on the same machine). But the Beacon Chain still sees Lido as having 275,000 validators in what some describe as “artificial decentralization.”

Artificial decentralization on the Beacon Chain is problematic for different reasons:

Problem #1: More computational resources are spent on processing consensus messages from the same (logical) entity since, as mentioned previously, deposits and attestations have to be processed on a per-validator basis. This increases the load on the p2p layer, which is now broadcasting redundant messages, and makes it difficult for consensus nodes to sync the chain.

Problem #2: Staking services and staking pools incur increased overhead from running multiple validators to maximize earnings. The process of consolidating rewards from existing validators into a new validator is also cumbersome—a new validator has to wait in the entry queue for a variable delay (which can be as long as a month or more), depending on the queue’s current capacity.

While problem #2 isn’t strictly a concern for protocol developers, problem #1 has negative implications for the health and stability of Ethereum’s consensus.

Higher bandwidth requirements can disincentivize solo staking due to the additional cost of investing in hardware upgrades. This creates the centralizing effect that the Beacon Chain’s design (e.g., 32 ETH as the minimum stake amount) was supposed to prevent.

Client developers may be forced to implement optimizations to deal with an increase in bandwidth and memory requirements, which increases the risk of bugs from frequent code rewrites and updates. Presently, consensus-related data like deposits, validator pubkeys, and attestations are directly stored in the Beacon Chain state and consensus clients must keep this state in memory to compute valid state transitions.

In worst-case scenarios, several validators may not process consensus messages fast enough to keep up with the rest of the chain and temporarily drop off the network. This can stall the Beacon Chain’s ability to finalize blocks, especially if the set of remaining validators doesn’t meet the 66% of stake threshold required to attest to a block before it achieves a notion of finality defined by Ethereum’s LMD-GHOST algorithm.

These aren’t theoretical concerns, with recent incidents highlighting the drawbacks of a large validator set:

Cascading Network Effects on Ethereum’s Finality discusses two non-finalization incidents, where the number of attesting validators dropped below 66% on July 22, 2023. While the root cause was a bug that caused consensus clients to spend computational resources on processing valid-but-old attestations, which prevented validators from processing newer attestations, the issue was likely exacerbated by the number of valid-but-old attestations processed by clients. If the number of attestations was low, clients could theoretically catch up faster with the network—although not as fast as if they were processing attestations from the current epoch.

In a Devconnect 2023 talk, Mike Neuder (researcher at the Ethereum Foundation and one of the authors of EIP-7251) discusses the experience of developers who ran a testnet with 2.1 million validators—where the chain was unable to finalize for long periods due to the inability of consensus clients to process a high number of attestations from validators. To put this discovery into context, the Beacon Chain is already close to 900,000 validators and, given current rates of deposits, will likely reach two million validators in the next few years.

Additionally, experiments have put upper bounds on the number of BLS signatures from validators that can be efficiently aggregated using state-of-the-art aggregation schemes like Horn. This has implications for future upgrades on Ethereum’s roadmap, such as single slot finality (SSF) and enshrined proposer-builder separation (ePBS), that rely on a threshold of attestations being broadcast and approved within a short window (e.g., single-slot finality requires aggregating and verifying signatures from supermajority of all validators (66% or more) in the 12-second duration of a slot).

EIP-7251 as a solution for reducing Ethereum’s validator set

Proposed solutions to the problem of an Beacon Chain unbounded validator set include:

Adjusting validator economics (e.g., reducing rewards). Since staking pools can spin up additional validators by combining rewards from old validators, reducing validator rewards can slow down the rate at which new validators are activated on the Beacon Chain.

Placing limits on the number of validators that can be active at any time. Once the validator set reaches capacity, a mechanism is activated to constrain an increase in the number of active validators and keep the validator set at the levels required for things like single-slot finality and enshrined PBS to function correctly.

Both approaches involve radical changes with significant consequences:

Approach #1 requires drastic changes to staking rewards and may have broad knock-on effects for the staking ecosystem. Approach #2 has tradeoffs depending on what happens when the validator set hits the preset limit: an “old validators stay” (OVS) scheme risks entrenching a set of validators—which can have consequences, even for short periods; a “new validators stay” (NVS) scheme introduces an MEV auction as validators would compete to enter the Beacon Chain (even older validators may be incentivized to compete with new entrants) in a post-MEV world where MEV revenue exceeds validator rewards .

However, there is another option that is simple enough to implement and effective at contracting Ethereum’s validator set. This solution is proposed in EIP-7251 and derives from a simple observation: we can curb artificial decentralization on the Beacon Chain by allowing multiple validators operated by the same entity to be consolidated into a single validator.

Consider a hypothetical node operator running four validators: in the current Beacon Chain specification, each validator has to individually sign blocks in the current Beacon Chain specification, which inflates the validator set as the same person controls all four validators. EIP-7251 proposes a validator consolidation mechanism that allows the node operator to merge the four 32 ETH validators into one validator with a total stake of 128 ETH.

This makes sense from the operator’s perspective as they only have to sign one message for the one validator they now control; it also makes sense from the network’s perspective: a 96 ETH validator can be treated as one validator (instead of four 32 ETH validators), which reduces the number of attestations processed by the consensus protocol. Significantly, it doesn’t change anything about the protocol—validators are still slashed and rewarded according to the amount staked (e.g., a 96 ETH validator is slashed differently from a 72 ETH validator)—and preserves existing guarantees of economic security.

But there are some blockers to implementing validator consolidation on Ethereum:

The current value of

MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE = 32 ETHis hardcoded into the Beacon Chain protocol and needs to change for validator consolidation to become a reality. Specifically,MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCEhas to increase by a significant factor (k) enough for validator consolidation to decrease the number of validators on the Beacon Chain’s validator substantially.No mechanism for signaling to the protocol that the balance of a validator (validator #1) should be added to the balance of another validator (validator #2) in-protocol exists. Validator #1 has to exit the Beacon Chain, after which validator #2’s balance can be increased via a “top-up” with funds from validator #1’s withdrawal. This is suboptimal from a UX perspective as a staking operator wishing to consolidate two or more validators has to exit those validators and combine their stakes to fund a new one.

EIP-7251 (appropriately named EIP-7251: Increase MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE) modifies the Beacon Chain’s specification and introduces a slew of changes necessary to implement and incentivize consolidation of validators on the consensus layer. In the next section, we’ll take an in-depth look at those changes before discussing the pros and cons of implementing EIP-7251—especially the proposal to increase MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE for validators.

An overview of EIP-7251: Increase MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE

EIP-7251 introduces a significant change to the core consensus protocol: an increase in MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE from 32 ETH to 2048 ETH (where k = 64). This removes the biggest blocker to the consolidation of validators and is arguably the most critical component of the plan to contract Ethereum’s validator set through validator consolidation.

But there are other features, beyond an increased maximum effective balance, that are needed to implement validator consolidation without decreasing existing security mechanisms or increasing operational overhead and risk for solo stakers and staking services. Thus, EIP-7251—contrary to what the EIP’s name suggests—does more than increase the maximum effective balance for validators. We’ll go through these changes in detail subsequently:

Note: This is intended to be a rough overview of changes proposed by EIP-7251 rather than an intensive explanation of the (current) specification. For a more detailed overview, I’ll encourage reading the draft specification and the FAQ document written by EIP-7251’s authors.

Increasing MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE and creating MIN_ACTIVATION_BALANCE

EIP-7251 updates MAX_EFFECTVE_BALANCE from the current value of 32 ETH to 2048 ETH, but it doesn’t change the minimum amount a validator needs to stake to join the Beacon Chain. This seems contradictory (or impossible), given that a validator’s eligibility for activation is currently determined by checking is eligible_for_activation queue() against MAX_EFFECTVE_BALANCE during Beacon Chain processing.

EIP-7251 resolves this contradiction by introducing a new constant MIN_ACTIVATION_BALANCE (set to 32 ETH) to represent the minimum effective balance required to activate a new validator and modifies is_eligible_for_activation_queue to check against MIN _ACTIVATION_BALANCE rather than MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE. This ensures solo stakers can continue to stake 32 ETH even with the new value for MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE and preserves the Beacon Chain’s economic decentralization.

An important caveat: EIP-7251 is purely opt-in; a validator that doesn’t update to the new 0x02 compounding withdrawal credential introduced by EIP-7251—and sticks with 0x01 credentials—will have MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE set to 32 ETH and receive partial rewards in the normal frequency. The next section discusses EIP-7251’s compounding withdrawal credential in more detail.

Introducing a new compounding withdrawal credential (0x02)

EIP-7251 introduces a new compounding withdrawal credential (0x02) to complement existing BLS withdrawal credentials (0x0) and execution-layer withdrawal credentials (0x01). The “compounding withdrawal” naming reflects that validators can compound rewards by switching to 0x02 credentials. Since rewards are computed to scale with effective balances, accruing a higher effective balance (up to the limit of MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE), instead of withdrawing excess balances above the minimum activation balance of 32 ETH, increases the validator’s rewards over time.

BLS_WITHDRAWAL_PREFIX = Bytes1('0x00')

ETH1_ADDRESS_WITHDRAWAL_PREFIX = Bytes1('0x01')

COMPOUNDING_WITHDRAWAL_PREFIX = Bytes1('0x02')The compounding withdrawal prefix is checked by the (now modified) is_partially_withdrawable_validator function that determines if a validator is eligible for an automatic partial withdrawal. If a validator has 0x02 credentials, the function get_validator_excess_balance compares the validator’s effective balance with MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE and returns any excess as the partial withdrawal amount. Note that MaxEB can be 2048 ETH or any value below 2048 ETH based on the validator’s preference (more on this feature later).

If a validator has 0x01 withdrawal credentials, get_validator_excess_balance compares the validator’s effective balance with MIN_ACTIVATION_BALANCE and returns any excess as the partial withdrawal amount. This preserves the functionality of automated partial withdrawals for solo stakers and minimizes disruption to the rewards skimming workflow for staking operators that continue to stake 32 ETH instead of staking higher amounts.

def get_validator_excess_balance(validator: Validator, balance: Gwei) -> Gwei:

/// Get excess balance for partial withdrawals for validator``

if has_compounding_withdrawal_credential(validator) and balance > MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE:

return balance - MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE

elif has_eth1_withdrawal_credential(validator) and balance > MIN_ACTIVATION_BALANCE:

return balance - MIN_ACTIVATION_BALANCE + return Gwei(0)Note: Details on how the migration from 0x01 withdrawal credentials to 0x02 compounding withdrawal credentials will work are still light—validators may be able to do a one-time change in-protocol (similar to 0x0 → 0x01 rotation), or need to withdraw and re-enter with new withdrawal credentials. I’ll update this article once core developers settle on a decision.

In-protocol combination of validator indices

EIP-7251 introduces a new consolidation operation that combines two validators into a single validator without requiring both validators to exit the Beacon Chain. A consolidation operation moves the balance of a source validator to a target validator and is signed by the source validator’s signing key.

Here’s a sketch of the consolidation operation from the EIP-7251 spec:

class Consolidation(Container):

source_index: ValidatorIndex

target_index: ValidatorIndex

source_signature: BLSSignature

source_address: ExecutionAddressThis change reduces overhead for solo stakers and staking pools that want to merge multiple validators without going through the cumbersome process of exiting validators from the active set and combining the withdrawn funds to activate a new validator. Consolidation operations are submitted by the source validator and processed like any other Beacon Chain operation (e.g., Deposit and VoluntaryExit) during each epoch. We’ll explain consolidation operations in more detail subsequently.

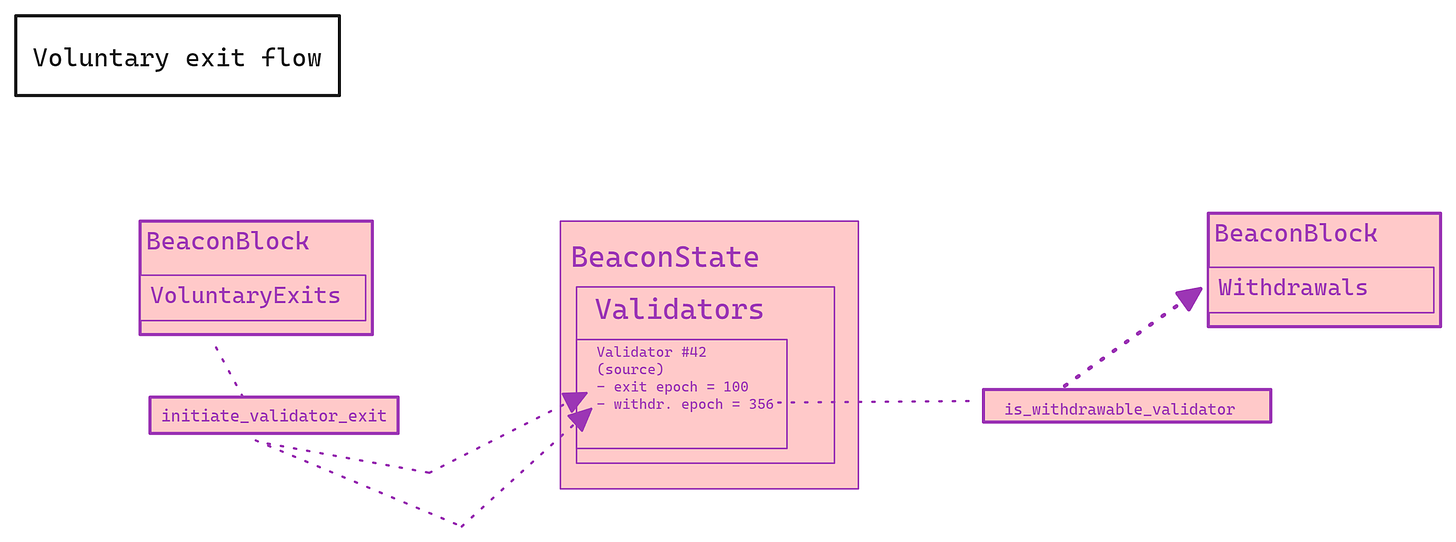

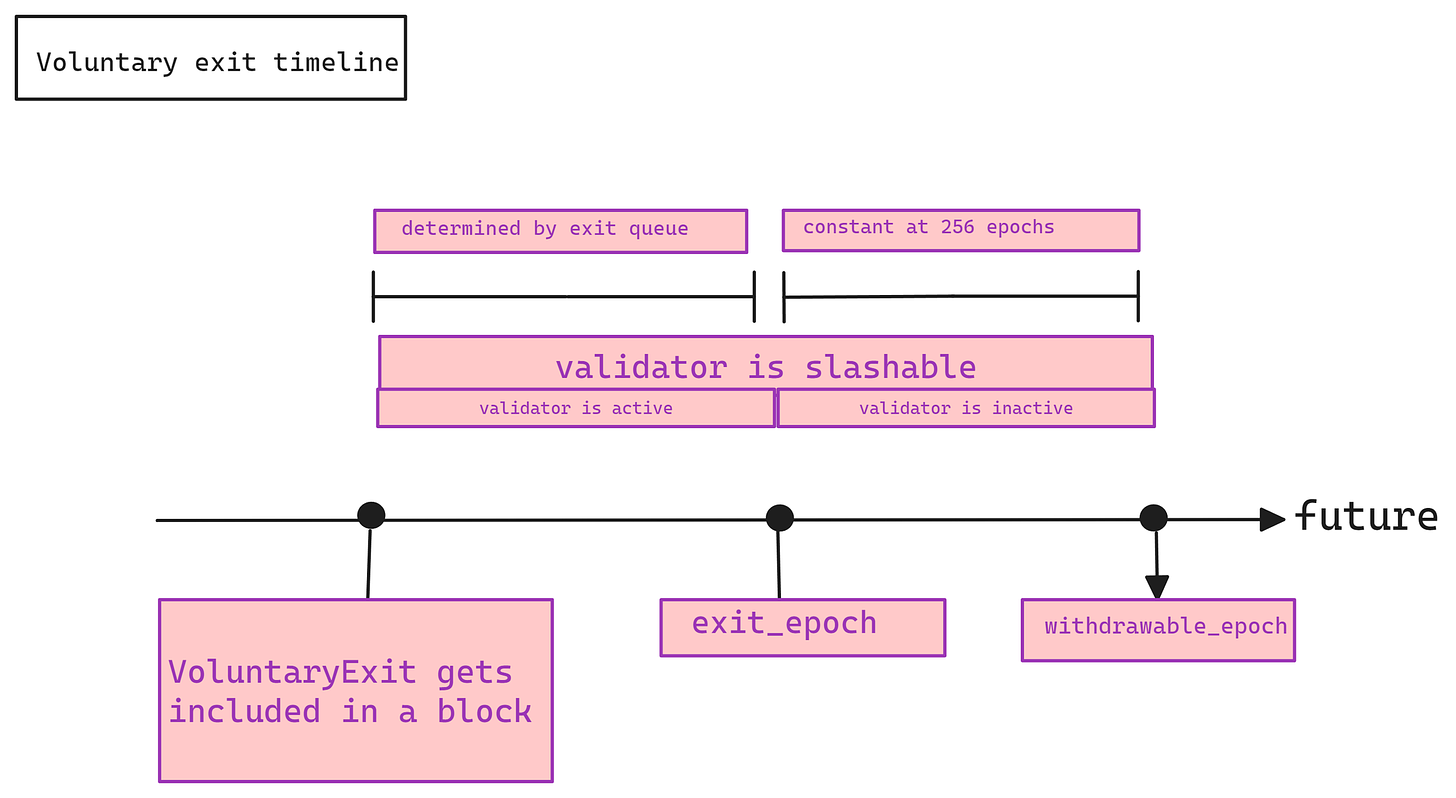

Recap: How does a voluntary validator exit work?

EIP-7251’s in-protocol consolidation operation uses elements of the existing VoluntaryExit operation, so it helps to understand how voluntary exits work before explaining in-protocol consolidation. Here’s a rough sketch of the voluntary exit procedure:

1. A validator signs a VoluntaryExit object and broadcasts it over the peer-to-peer network for inclusion in a Beacon block. The initiate_validator_exit function is called during Beacon block processing and sets the exiting validator's exit_epoch and withdrawable_epoch in the BeaconState.

Having successfully signaled an intent to leave the active validator set, the exiting validator is placed in the exit queue (exit_queue). How long a validator waits in the exit queue before fully withdrawing from the Beacon Chain depends on the churn limit and the number of pending validator exists. We’ll go over the churn limit specification in a later part of the article and see how it affects validator exits (in the status quo and when EIP-7251 is activated).

The validator is expected to continue performing consensus duties (e.g., attesting to blocks and participating in committees) while waiting to leave the exit queue. This delay is defined by the exit_epoch: the epoch during which an exiting validator becomes inactive and can stop performing Beacon Chain duties. Note that the validator is still earning rewards while waiting in the exit queue.

2. While validators stop attesting/proposing after exit_epoch, they cannot withdraw staked ETH until the withdrawable_epoch is reached. The withdrawable epoch is calculated by adding MIN_VALIDATOR_WITHDRAWABILITY_DELAY to exit_epoch: the minimum validator withdrawable validator delay is set to a constant of 256 epochs (roughly 27 hours), so an exiting validator must wait a duration of exit_epoch + MIN_VALIDATOR_WITHDRAWABILITY_DELAY before withdrawing completely from the Beacon Chain.

At the beginning of the withdrawable_epoch the validator’s balance is transferred to the execution-layer address specified in the withdrawal credentials. Note that the validator doesn’t earn rewards after the exit epoch—but it can still be slashed for offenses committed in the past until the withdrawal is processed at the withdrawable_epoch. Imposing a minimum delay of 27 hours provides enough time detect protocol-violating behavior and prevents faulty validators from exiting stakes without incurring penalties for historical offenses.

The graphic below shows the timeline for a voluntary exit operation:

How does in-protocol validator consolidation work?

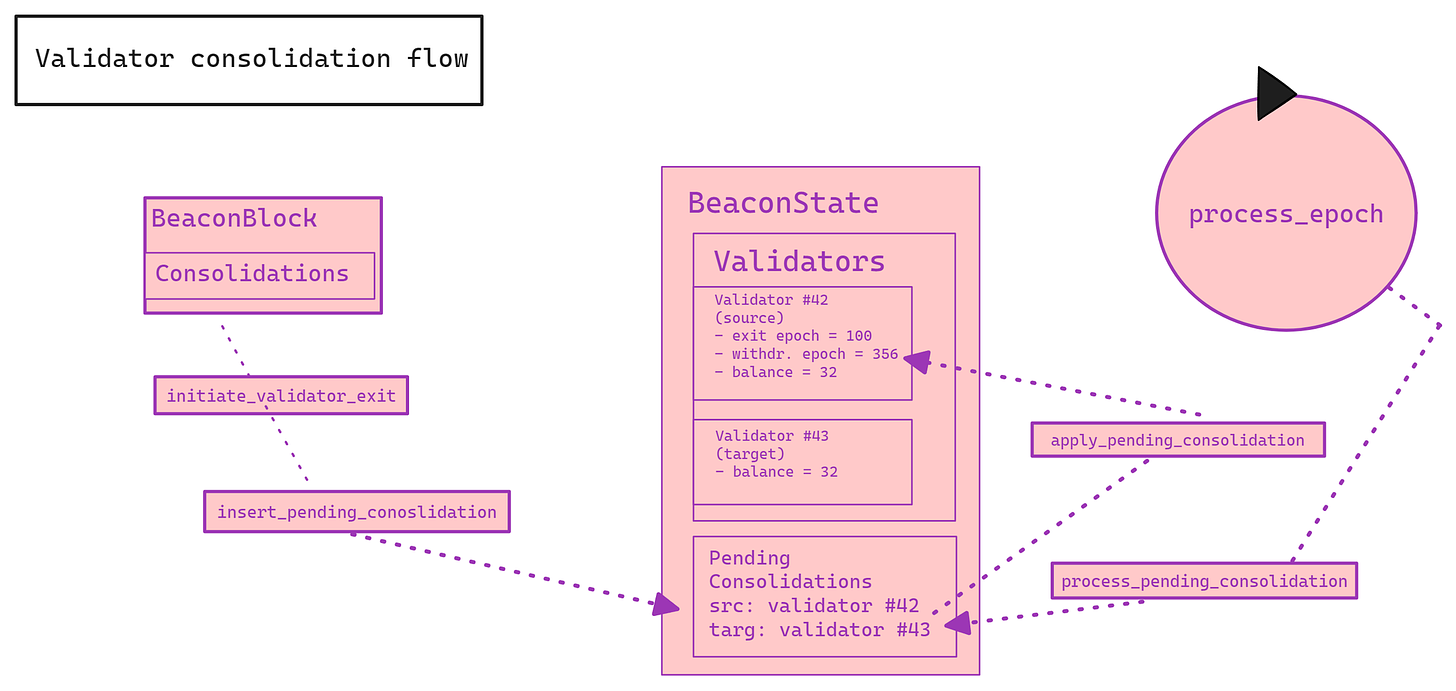

EIP-7251 slightly modifies the mechanics of a VoluntaryExit operation for validators that signal a desire to consolidate with another validator. The figure below describes the process of consolidating two validators in-protocol:

We’ll establish some terms:

source: The validator that wishes to allocate its effective balance to atargetvalidator.target: The validator that accumulates the balance of asourcevalidator.Consolidation: An object signed by thesourceandtargetvalidators to signal an intent to consolidate their balances without exiting the protocol.

Here’s a sketch of the consolidation process:

1. Like a regular VoluntaryExit message, the signed Consolidation object must be broadcasted over the peer-to-peer network and included in a Beacon block to start the process of moving the source validator’s balance to the target validator. The initiate_validator_exit function is called during the processing of the Beacon block that includes the signed Consolidation object and triggers a voluntary exit for the source validator.

When initiate_validator_exit is called, the source validator’s exit epoch and withdrawable epoch are set in the Beacon State. insert_pending_consolidation is also called during block processing to insert a pending_consolidation for the source and target validator in the Beacon state.

2. While the source validator is waiting in the exit queue, it must continue performing Beacon Chain duties until the withdrawable epoch. But, instead of sending the validator’s balance to the withdrawal address, we allocate it to the target validator and increase the latter’s effective balance.

The transfer of funds happens during epoch processing (process_epoch → process_pending_consolidation). Here, apply_pending_consolidationis called to move the source validator’s balance to the target validator’s balance and finalize the consolidation process.

3. The consolidation operation is authenticated by checking that both source and target validators have the same withdrawal address. Confirming that a source and a target validator have the same withdrawal address is a simple way to determine if both validators are controlled by the same entity. This way, we know that all parties approve of the consolidation operation and no one is forcefully moving a validator’s balance without permission.

This particular edge-case (invalid consolidation operations) can appear if we solely rely on signatures from a validator’s signing key to authenticate consolidation operation. For example, an attacker can compromise the signing key and sign a rogue Consolidation object that moves the validator’s balance to the attacker’s target validator.

However, requiring validators in a pairwise consolidation to share the same withdrawal credentials creates issues for staking pools and staking companies that don’t reuse withdrawal credentials, or map validators to multiple withdrawal addresses (instead of a single withdrawal address). For instance, a staking pool controlling two 32 ETH validators with different withdrawal addresses will need to exit both validators and re-enter the Beacon Chain with a new 64 ETH validator.

An alternative is to verify signatures from the withdrawal key of the source and target validators on the Consolidation message. Since the withdrawal key has ultimate ownership of staked ETH, a signature from the withdrawal key of either validator provides evidence we need to approve a consolidation—even if source and target validators have different withdrawal credentials.

But this requires implementing a mechanism for verifying execution-layer signatures on the Beacon Chain (the consensus layer uses a BLS12-381 curve, while the execution layer uses the Sepc256k1 curve) or introducing a mechanism for consolidation operations to be verified on the execution layer (similar to EIP-7002 withdrawals processed on the EL). Both approaches introduce extra complexity, which already “touches many parts of protocol” as some have described it.

It’s possible this part of the consolidation operation specification will change, especially as large staking pools like RocketPool (which uses > 1000 deposit addresses to fund validators controlled by node operators) may find it difficult to consolidate under the current design. If that happens, I’ll update this document to reflect changes to the spec.

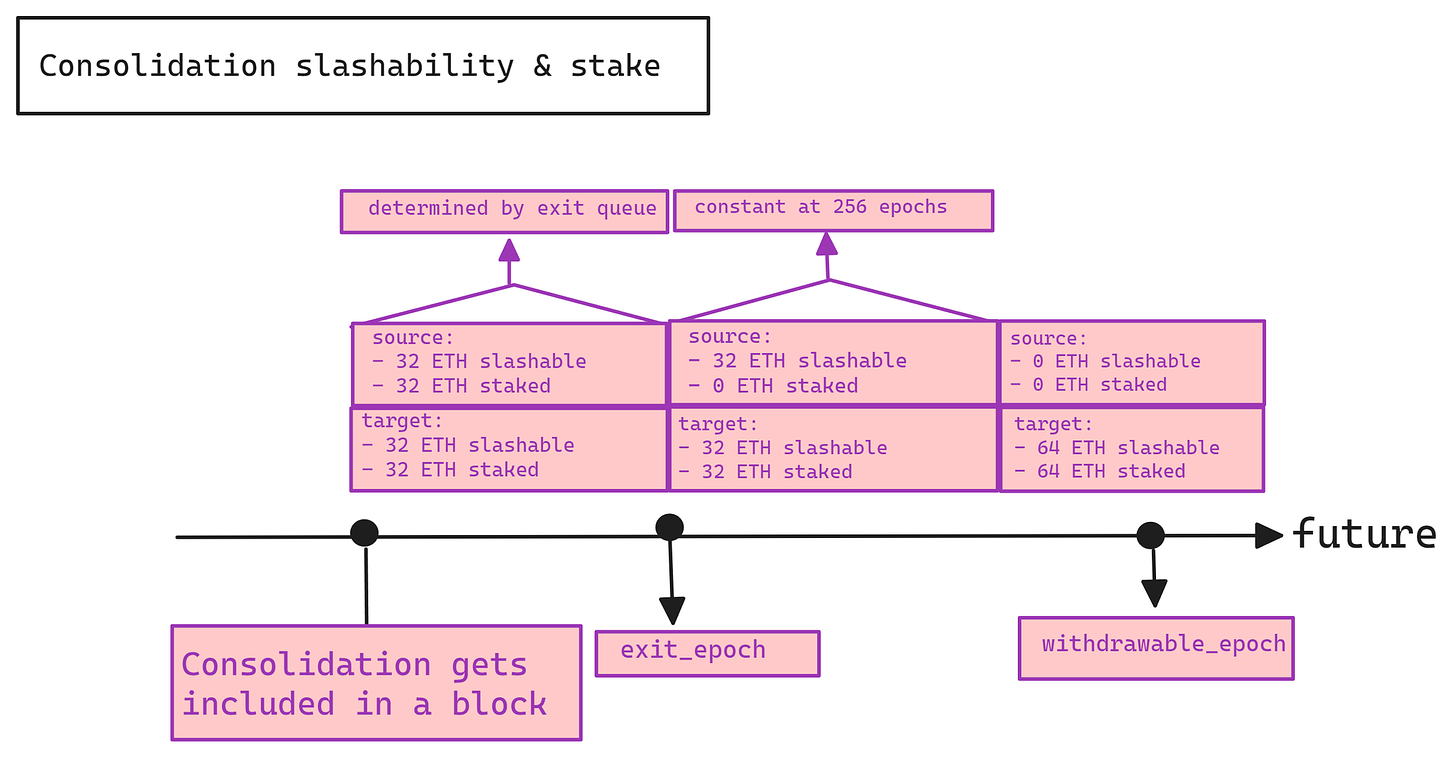

How does slashing work when validators are consolidating?

In-protocol consolidation doesn’t change much about the slashing process. As with a VoluntaryExit, the source validator is slashable for its original balance (the initial effective_balance) until it reaches the assigned withdrawable epoch. The target validator is also slashable for its initial effective_balance—at least until we reach the withdrawable_epoch of the source validator.

At this point, the source validator’s balance is transferred to the target validator and the latter becomes responsible for the aggregate (consolidated) balance of both validators. If the target validator commits a slashable offense during the source validator’s withdrawal epoch (after balances have been merged), it is slashed proportionally to its effective_balance after consolidation.

Below is a graphic describing how slashing is attributed during the consolidation period:

Permitting validators to set custom ceilings for MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE

The withdrawal of a validator’s balance, once it exceeds MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE, to the withdrawal address is a system-level operation that occurs automatically and doesn’t require a validator to initiate a transaction. Notably, the partial withdrawal sweep offers stakers a gasless mechanism for “skimming” rewards from the consensus layer, and provides a reliable source of income stakers rely on to cover operational costs (among other things).

Changing MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE from 32 ETH to 2048 ETH potentially increases the delay for partial withdrawal sweep, especially for solo stakers and staking pools that may not immediately reach the 2048 ETH ceiling (you can imagine how long it’ll take a solo staker to accrue enough rewards to reach a balance of 2048 ETH). To ensure an increase in MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE doesn’t impact stakers negatively, EIP-7251 proposes a new feature that will allow validators to set custom values for MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE and control when the partial withdrawal activates.

To clarify, the default maximum effective balance for validators that migrate to 0x02 compounding withdrawal credentials is still 2048 ETH. However, an 0x02 validator can set a custom value below 2048 ETH for MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE which the Beacon Chain’s (modified) is_partially_withdrawable_validator function can check to determine if a validator is due for a partial withdrawal sweep.

A useful (albeit possibly inaccurate) mental model is to think of 0x02 validators as having two types of maximum effective balance (MaxEB) in a post-EIP 7251 world—a constant MaxEB and a variable MaxEB—that determine when the partial withdrawal occurs:

Partial withdrawals after the constant MaxEB of 2048 ETH is the default behavior for validators that increase

MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCEby changing to0x02credentials and don’t specify a custom ceiling for maximum effective balance.Partial withdrawals after the variable MaxEB for an

0x02validator occurs whenever the effective balance crosses the value ofMAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCEset by the validator. EIP-7251 permits validators to set any value for the variable MaxEB—provided the chosen value doesn’t exceed 2048 ETH.

Permitting variable ceilings for the maximum effective balance ensures stakers can continue to rely on gasless automatic withdrawals(“skimming”) as a source of income. It also makes adopting EIP-7251 attractive for solo stakers and staking services that prefer skimming to the alternative for partially withdrawing validator balances under EIP-7251: execution-layer partial withdrawals (which we discuss next).

Adding execution-layer partial withdrawals

EIP-7002 introduces the concept of execution-layer exits: a staker can exit their validator from the Beacon Chain by sending an exit transaction—signed with the validator’s withdrawal credential—to a “validator exit precompile” on the execution layer. Exit messages are added to a queue, and the ExecutionPayload of a Beacon block consumes several exit messages from this queue up to the value of MAX_EXITS_PER_BLOCK (16). You can read EIPs for NERDS #3: EIP-7002 (Execution Layer Triggerable Exits) for a comprehensive overview of execution-layer triggered exits, especially to understand how they compare to voluntary exits triggered on the consensus layer.

EIP-7002 is currently designed to work for full validator withdrawals similar to a VoluntaryExit signed by a validator’s signing key: an execution-layer exit triggers the withdrawal of a validator’s balance to the withdrawal address. However, the authors of EIP-7251 propose an extension to EIP-7002 that will allow a staker to trigger partial withdrawal of a validator’s balance by sending a transaction on the execution layer. With this feature, an 0x02 validator can withdraw arbitrary amounts over MIN_ACTIVATION_BALANCE (32 ETH) without necessarily waiting for the partial withdrawal sweep to activate.

This is another attempt to mitigate the effects of an increase in MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE for stakers and reduce the barrier to adopting EIP-7251. To see why this is important, consider the status quo: the automatic sweep at 32 ETH provides a steady stream of liquidity and enables staking pools to frequently do things like payout rewards to stakers. In comparison, with the maximum effective balance updated to a constant of 2048 ETH per EIP-7251, the automatic sweep will happen less frequently for validators that increase their maximum effective balance.

EIP-7251’s variable MaxEB feature alleviates but doesn’t completely fix the problem, either. Suppose an 0x02 validator sets 128 ETH as the custom maximum effective balance and receives a partial withdrawal when MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE crosses 128 ETH. Now, imagine the same validator’s effective balance drops from 128 ETH to 80 ETH for some reason (e.g., getting slashed for downtime)—that validator needs to accrue at least 48-49 ETH to become eligible for another partial withdrawal.

This could be better from the perspective of a staker or staking pool that needs enough liquidity to run a profitable staking operation. Allowing stakers to partially withdraw balances via withdrawal credentials—using the mechanism for passing messages between the execution layer and consensus layer provided by EIP-7002—fixes this problem. Validators can now withdraw arbitrary amounts from the validator_effective_balance without exiting contingent on specific requirements:

The withdrawer (identified by the withdrawal credential) pays the required gas fee for the withdrawal transaction on the execution layer. Current estimates peg the cost of a partial EL withdrawal at 50,000 gas (inclusive of the fixed

base_feeof 21,000 gas).The remaining balance is higher than

EJECTION_BALANCE(16 ETH); any validator whose balance drops below 16 ETH is automatically placed in the exit queue and forcefully exited.

We can illustrate the value of execution-layer partial withdrawals by considering the previous example of a validator with a variable MaxEB of 128 ETH. Instead of waiting until 80 ETH increases to 128 ETH to withdraw, the validator can elect to withdraw from the existing balance of 80 ETH (insofar as it doesn’t drop below the ejection balance) by triggering a withdrawal operation from the execution layer.

One question that may arise is: “What happens if validators start moving large amounts of stake around—what would that mean for Ethereum’s (economic) security?” This is a legitimate concern, especially if we consider the possibility of bad actors exploiting the freedom to transfer sizable funds between the consensus and execution layers quickly. But there’s an even less theoretical concern: specific security properties of Ethereum’s consensus protocol depend on the assumption that the amount of stake exiting the protocol cannot exceed a defined threshold in a particular time window.

Without a mechanism to rate-limit partial withdrawals of validator stakes, implementing EIP-7251 may break certain invariants critical to the security of Ethereum’s consensus protocol. Fortunately, the authors of EIP-7251 have considered this edge case and proposed modifications to the mechanism for rate-limiting withdrawals and deposits on the Beacon Chain—we will discuss this feature next.

Using weight-based rate limiting for exit and deposit queues

Proof of Stake protocols with Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) have accountable safety if adversarial actions—like finalizing two conflicting blocks—cannot occur without the protocol slashing ⅓ * n of validator stakes where n is the total active stake. Since ⅔ * n stake is required to finalize blocks, two conflicting blocks appearing at the same height in an epoch n means at least ⅓ of the active stake must have voted twice for different blocks b and b’.

Signatures are cryptographically linked to each validator’s public key, so an honest party can prove which validators double-signed during the epoch. But, for the Proof of Stake protocol to slash the offending validators, a supermajority (⅔ * n) validators have to finalize a block b+1 in the next epoch e+1 that contains evidence of double-signing. This means an attacker must not control ⅔ * n (or more) of the total active stake, or it can choose to finalize a different block that doesn’t include evidence from the whistleblower.

Thus security relies on the assumption that the total active stake cannot change by more than ⅓ * n between epochs n and n+1—otherwise, an adversary can potentially increase its share of the total stake n from ⅓ * n to ⅔ * n. This is why PoS protocols like Gasper require a mechanism for rate-limiting inflow and outflow of stake during epoch transitions; importantly, rate-limiting parameters must be carefully chosen as they determine the level of economic security the consensus protocol provides.

Note that the rate-limiting mechanism doesn’t care about the number of validators joining or exiting during epochs and focuses on changes to the validator weight (i.e., the amount of stake) during the boundary between epochs n and n+1. The importance of this detail will become evident as we discuss changes to the rate-limiting mechanism proposed by EIP-7251.

Validator churn limits under EIP-7251

Today, the Beacon Chain’s churn limit (i.e., the maximum number of validator activations and exits per epoch) is determined by the get_validator_churn_limit function. get_validator_churn_limit is influenced by two parameters: MIN_PER_EPOCH_CHURN_LIMIT = 4 and CHURN_LIMIT_QUOTIENT = 65,536 (2**16).

The first parameter, MIN_PER_EPOCH_CHURN_LIMIT, indicates that each epoch can have at least four validator entries and exits; the second parameter, CHURN_LIMIT_QUOTIENT, is more critical and limits the maximum validator churn per epoch by setting it to 1/65536 (roughly 0.0015%) of the active validator set—provided at least four validators are active.

However, the current parameters for the get_validator_churn_limit functions will become insufficient for Gasper’s accountable safety property once EIP-7251 implements variable maximum effective balances. Why? The existing rate-limiting mechanism is designed to limit the number of validators exiting and joining the active validator set and not the weight leaving and entering the active set.

We can get away with this currently because setting MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE to a constant of 32 ETH (which is also the minimum activation balance for validators) introduces a rough correlation between validator weights and validator numbers. For example, 1/65536 of Beacon Chain validators (897,892 validators at the time of writing) is ~13 validators—since a validator can have at most 32 ETH as maxEB, this translates to about 438 ETH flowing in and out of the protocol per epoch under current churn-limit rules (13 validators * 32 ETH). Calculating 438 ETH as a percentage of the total stake (28,732,281 ETH at the time of writing) gives us roughly 0.0015% or 1/65536—which correlates to the value of CHURN_LIMIT_QUOTIENT.

But increasing the constant maxEB to 2048 ETH, and introducing variable maxEBs (which can be higher than the minimum activation balance of 32 ETH), breaks this invariant:

Suppose we use the previous per-epoch churn limit of 13 validator exits/activations and assume all validators scheduled for exiting during an epoch n have a MaxEB of 2048 ETH. A total of 13 validators exiting per epoch would equal 26,624 ETH of stake leaving the active set (13 * 2048 = 26624).

Calculating 26,624 ETH as a percentage of the total stake (28,732,281 ETH at the time of writing) gives us 0.0092% or roughly 1/1000 of the stake—which is ~64x faster than the current churn limit of 1/65536. To put this into into context, it would take just 356 epochs (~37 hours) to exit ⅓ x n (33%) of the total stake (at 2048 ETH per validator) compared to the 21,647 epochs (96 days) it would take to withdraw 33% of the active stake under the existing churn limit (at 32 ETH per exited validator).

To preserve the churn limit invariant, EIP-7251 modifies get_validator_churn_limit to account for the balances (total weight) of all active validators instead of accounting solely for the number of active validators. get_validator_churn is now a Gwei value instead of a uint64 value and the MIN_PER_EPOCH_CHURN_LIMIT function for setting the maximum validator churn for an epoch uses total_active_balances (aggregate stake of active validators) as input instead of active_validator_indices (total number of active validators) as shown below:

return max(MIN_PER_EPOCH_CHURN_LIMIT * MIN_ACTIVATION_BALANCE, get_total_active_balance(state) // CHURN_LIMIT_QUOTIENT)The churn limit is multiplied by the total active stake to determine the maximum weight that can enter and exit during an epoch.

EIP-7251 also modifies the exit and activation queues to use weight-based rate-limiting and changes how validator_exit_epoch and validator_activation_epoch—which indicate the epoch for exiting and activating a validator, respectively—are computed. First, it introduces a new value, activation_validator_balance, that tracks the balances of the validator at the head of the activation queue and modifies exit_queue_churn (now in Gwei) to track balances of validators to be exited in the current epoch. It also creates two values, exit_balance_to_consume and activation_balance_to_consume, to account for situations where the stake of a joining or exiting validator exceeds the per-epoch churn limit.

We’ll see how the new weight-based rate limiting for activation queues and exit queues works shortly:

Validator activations under EIP-7251

Validators are activated during the process_registry_updates phase of the Beacon Chain’s epoch transition workflow. The value of activation_balance_to_consume is a function of the epoch churn limit (per_epoch_churn_limit), activation validator balance (activation_validator_balance), and effective balance of the previously activated validator. We can understand this concept by using details from the previous example:

The current epoch churn limit is 438 ETH, and the effective balance of the validator at the front of the activation queue is 200 ETH. This means

activation_validator_balanceis 200 ETH andactivation_balance_to_consumefor the current epoch is 238 ETH (activation_balance_to_consume=per_epoch_churn_limit-activation_validator_balance).The next validator in the queue has an effective balance of 100 ETH, which is lower than the

activation_balance_to_consume(238 ETH). We schedule the second validator for activation during this epoch and decreaseactivation_balance_to_consumebyvalidator_effective_balanceto leave the epoch’sactivation_balance_to_consumeat 138 ETH.activation_validator_balanceis now 300 ETH.The third validator in the queue has an effective balance of 250 ETH and cannot be activated in this epoch as

validator_effective_balance(250 ETH) exceeds the current epoch’sactivation_balance_to_consumethreshold (138 ETH). By extension, this implies that activating the third validator will violate the epoch churn limit invariant asvalidator_effective_balance+activation_validator_balance= 550 ETH, which is above the per-epoch churn limit of 438 ETH.We subtract the epoch’s

activation_balance_to_consumefromvalidator_effective_balanceand roll the remaining validator balance to the next epoch. Theactivation_validator_balancefor epoch n + 1 is set to 112 ETH to reflect the churn caused by the leftover validator balance from the previous epoch n.To get the

activation_balance_to_consumefor epoch n + 1, we subtractactivation_validator_balancefromper_epoch_churn_limit, which gives us 326 ETH. The value of validator #3’s unprocessed effective balance (112 ETH) is lower than the epoch churn limit (438 ETH), so we can schedule the validator for activation during epoch n +1.

Validator exits under EIP-7251

EIP-7251 modifies the initiate_validator_exit() function to account for the validator’s weight before computing the exit_queue_epoch (i.e., the epoch where the validator can exit and fully withdraw). Furthermore, exit_queue_churn is modified to accumulate balances of validators leaving in the current epoch, and exit_balance_to_consume tracks the balance of the validator at the head of the exit queue.

def initiate_validator_exit(state: BeaconState, index: ValidatorIndex) -> None: ... # Compute exit queue epoch exit_epochs = [v.exit_epoch for v in state.validators if v.exit_epoch != FAR_FUTURE_EPOCH]

exit_queue_epoch = max(exit_epochs

exit_balance_to_consume = validator.effective_balance

per_epoch_churn_limit = get_validator_churn_limit(state)

if state.exit_queue_churn + exit_balance_to_consume <= per_epoch_churn_limit:

state.exit_queue_churn += exit_balance_to_consume

else: # Exit balance rolls over to subsequent epoch(s)

exit_balance_to_consume -= (per_epoch_churn_limit -state.exit_queue_churn)

exit_queue_epoch += Epoch(1) + while exit_balance_to_consume >= per_epoch_churn_limit:

exit_balance_to_consume -= per_epoch_churn_limit

exit_queue_epoch += Epoch(1)

state.exit_queue_churn = exit_balance_to_consume

# Set validator exit epoch and withdrawable epoch

validator.exit_epoch = exit_queue_epoch validator.withdrawable_epoch = Epoch(validator.exit_epoch + MIN_VALIDATOR_WITHDRAWABILITY_DELAY)Putting these details together provides a picture of how exits (full withdrawals) work in a post-EIP 7251 world:

When a validator initiates an exit, the

initiate_validator_exitfunction checks thatvalidator_effective_balanceis within the current epoch’sper_epoch_churn_limitthreshold. If the balance is within limits,exit_queue_churnis increased byvalidator_effective_balance, and the validator’s exit queue epoch is set to the current epoch.If a validator’s effective balance is larger than

per_epoch_churn_limit, we decreasevalidator_effective_balancebyper_epoch_churn_limitto compute the next epoch’sexit_balance_to_consume. During the next epoch, we check ifexit_balance_to_consume(i.e., the validator’s unprocessed balance from the previous epoch) is lower thanper_epoch_churn_limit; if so, the validator’s exit queue epoch is set that epoch.If

exit_balance_to_consumestill exceeds the per-epoch churn limit, we keep increasingexit_queue_epochand decrease the exit balance untilper_epoch_churn_limitis greater thanexit_balance_to_consume. At this point, the validator’s remaining balance can be processed for exiting in the current epoch without violating the limit imposed by the per-epoch churn limit.

We can understand this concept by using a similar example from the section on activations:

The epoch churn limit is 438 ETH, and the next validator in the exit queue has a maxEB of 2048 ETH;

exit_balance_to_consumeis higher than the epoch churn limit, so the validator cannot exit in the current epoch n. We subtractper_epoch_churn_limitfromexit_balance_to_consumeat epoch n to get theexit_balance_to_consumefor the next epoch n + 1.At epoch n + 1, the

exit_balance_to_consume(1172 ETH) still exceedsper_epoch_churn_limit. We decreaseexit_balance_to_consumebyper_epoch_churn_limitonce again and repeat the process until we reach epoch n + 3 whereexit_balance_to_consume(now at 296 ETH) is lower than the per-epoch churn limit. This will be the validator’s exit queue epoch.The

exit_queue_churnfor epoch n + 3 is set to 296 ETH to reflect the churn from processing the remainder of the validator’s effective balance (i.e., what’s left ofexit_balance_to_consume) in that epoch.

Changes to the activation and exit queues proposed by EIP-7251 ensure that large validators can be processed for full exits or activation over multiple epochs. More importantly, computing exit and activation epochs mean validators can variable activation balances and effective balances without breaking the property that at most 1/65536 of the total active stake can exit/enter the Beacon Chain’s active set.

Partial deposits and withdrawals under EIP-7251

So far, we’ve discussed how EIP-7251 addresses the problem of variable activation and effective balances among validators exiting and joining the Beacon Chain and implements measures to preserve Gasper’s economic security properties. But how does it handle partial deposits and withdrawals, as validators potentially have more ETH to partially withdraw once MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE is increased to 2048 ETH and the variable maxEB feature is implemented?

Like validators exiting or joining with enormous stakes, large amounts of stake flowing in and out of the protocol via partial withdrawals and deposits (a.k.a., “validator top-ups”) can be problematic. For background: partial deposits skip the activation queue and are capped at MAX_DEPOSITS = 16 per block, which is higher than the limit on validator activations.

This isn’t a problem under the status quo: if an attacker can introduce more than ⅓ * n of stake into the protocol via top-ups, then it must have lost an equal amount of stake previously. Recall that all validators must deposit a minimum of 32 ETH as collateral, and the maximum effective balance cannot exceed 32 ETH.

To illustrate: Imagine a miniature version of the Beacon Chain with nine validators and 288 ETH in total stake (at 32 ETH per validator): ⅔ of validators are honest, and ⅓ of validators are controlled by an adversary, which means 192 ETH of the total active stake is honest, and 96 ETH of the total active stake is adversarial. Suppose the attacker wants to increase its balance by over ⅓ of the total active stake (96 ETH) during an epoch. In that case, the three validators it controls must currently have balances of 0 ETH, and a validator can drop to 0 ETH only if the protocol slashes it.

That said, keeping the minimum activation balance at 32 ETH and increasing the maximum effective balance changes the dynamics. To use the previous example, an attacker can deposit 56 ETH per validator to increase the total stake of adversarial validators to 264 ETH and the total active stake to 392 ETH; if the remaining validators don’t top up, the adversary now controls > ⅔ of the stake and can block a mass slashing event.

EIP-7251 requires partial deposits to go through the activation queue and rate-limits top-ups with the weight-based rate-limiting mechanism introduced earlier to prevent this edge case. This prevents an attacker from using balance top-ups to circumvent the activation queue and keeps churn within limits defined by get_validator_churn_limit. However, this means validators that don’t increase MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE will now experience a variable delay on balance top-ups (depending on activation queue congestion).

An alternative proposal is to cap partial deposits at 32 ETH so that 0x02 validators can only increase effective balances up to MIN_ACTIVATION_BALANCE via top-ups. This would preserve the original behavior of partial deposits and probably eliminate the need to rate-limit top-ups; plus, validators that don’t adopt EIP-7251 can continue to use top-ups to quickly replenish balances and avoid losses from a drop in effective balances (Understanding Validator Effective Balance explains the connection between effective balance and changes in validator rewards in detail).

However, limiting top-ups to 32 ETH has a greater impact on validators that do increase MaxEB and results in poor UX: (1) Validators with a MaxEB higher than 32 ETH cannot replenish the effective_balance if it reduces due to a slashing or penalty event. (2) Validators can no longer top-up to increase effective_balance in typical situations and must exit before activating with a higher effective balance.

Partial execution-layer withdrawals under EIP-7251 will follow the same pattern of weight-based rate limiting as total withdrawals triggered with a validator’s signing key. For context, full exits triggered from a validator’s withdrawal credentials are rate-limited by default: EL-triggered exit messages are added to the exit_queue on the Beacon Chain and processed the same way as VoluntaryExit messages. Partial EIP 7002-style exits will go through the exit_queue as well, so rate-limiting partial withdrawals under EIP-7251 is relatively straightforward.

Modifying initial slashing penalty and correlation penalties

The initial slashing penalty (applied by the slash_validator() function) is the first reduction applied to the balance of a balance of a validator that commits a slashable offense and is linearly proportional to the validator’s effective balance. For example, a validator with an effective balance of 32 ETH will have an initial penalty of 1/32 or 1 ETH.

The initial slashing penalty is one part of the Beacon Chain’s slashing mechanism but is arguably the most important in the context of EIP-7251. To illustrate, a validator with an effective balance of 2048 ETH will lose 64 ETH as part of the initial slashing penalty (1/32 * 2048 = 64). This increases the risk for large validators with higher effective balances—which puts us in a difficult situation since EIP-7251 primarily aims to encourage staking pools to run larger validators.

The current proposal to address this problem is to modify slash_validator to apply a constant reduction (1 ETH) or scale sublinearly—instead of linearly—in proportion to the validator’s effective balance. The first proposal ensures every validator loses exactly 1 ETH the first time they’re slashed; however, this is arguably less of a credible threat to disincentivize slashable behaviors compared to the original 1/32 slashing function (e.g., a 2048 validator loses the same amount of ETH as a 32 ETH validator).

In comparison, scaling initial slashing penalty to increase sublinearly preserves the guarantee that validators with larger balances are punished proportionally without necessarily increasing the risk for validators with larger balances. The slashing penalty analysis from Mike Neuder et al. shows how different values for a sublinearly scaling initial slashing penalty can be chosen to balance economic security with the goal of encouraging validators to participate in protocol-beneficial behavior like validator consolidation.

The slashing analysis document also addresses another issue: under current slashing rules, validators with a larger effective balance are likely to suffer higher correlation penalties. Upgrading Ethereum has more information on correlation penalties—in the meantime, you can think of a correlation penalty as a deterrent to disincentivize validators from joining in a coordinated attack on the protocol (if a validator is slashed, and many validators are slashed for a similar offense around the same period, the correlation penalty is applied before the validator’s withdrawal epoch).

Correlation penalties are critical to the guarantee that the protocol can destroy ⅓ of the total active stake for offenses like finalizing two conflicting blocks. For example, the correlation penalty is designed so that a validator’s entire balance can be slashed if ⅓ of validators are slashable for the same offense (effective_balance is one of the inputs to the correlation penalty function), which makes sense in the status quo where every validator has the same maximum effective balance of 32 ETH.

The assumption that every validator has a MaxEB of 32 ETH breaks down once EIP-7251 is implemented and validators increase effective balances. But the real concern is that effective_balance is one of the inputs to the correlation penalty function, which puts consolidated validators with larger effective balances at a disproportionate risk of suffering higher correlation penalties in a mass slashing scenario.

To mitigate this problem, EIP-7251 proposes to modify the correlation penalty to scale quadratically instead of linearly in proportion to the validator’s effective_balance. The “correlation penalty” section of slashing penalty analysis shows that quadratically scaling correlation penalties preserves concrete security guarantees, especially in ⅓-slashable scenarios, but reduces the risk for individual validators with higher effective balances.

To sum up, EIP-7251 doesn’t exactly change the slashing penalty to solely favor large validators—a validator with more collateral at stake will still have more to lose in a slashing than a validator with a small stake. This is the expected behavior of any Proof of Stake protocol with meaningful economic security, or any arrangement where “how much you get is how much you put in” (higher risk = higher rewards). However, adjusting the system of applying penalties achieves the following goals:

Aligns cryptoeconomics of slashing with the new reality of higher effective balances

Brings down slashing risk to levels that large validators can tolerate and increases the likelihood of more validators opting to consolidate stake

Why EIP-7251? The case for increasing MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE

Most of the benefits of implementing EIP-7251 are evident from discussions in previous sections. But a summary of the net benefits of increasing MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE for validators to the network and stakers may be helpful, especially if you skipped to the part where you learn “what’s in it for me for me as a solo staker/staking service operator?”

Reduced load on the consensus layer

Aditya Asgaonkar’s Removing Unnecessary Stress from Ethereum’s P2P Network post provides a good overview (from the perspective of a protocol developer) of the burden having a large number of validators places on the Beacon Chain’s p2p networking layer. For instance, a large validator set increases the number of messages broadcasted and gossiped over the network and the number of attestations to aggregate and verify in each epoch. These factors combined could increase compute and bandwidth requirements for validator nodes, degrade network performance, and ultimately hurt decentralization.

Similarly, Dapplion’s Beacon Node Load as a Function of Validator Set Size post provides a client developer’s perspective on the problem with a large validator set, which is helpful for discussing the intersection of network performance and decentralization:

As noted in the document, consensus clients must keep certain parts of the Beacon State (e.g., deposit messages and validator pubkeys) in working memory for consensus clients to process blocks. Increases in the validator set correlate to increases in the size of the Beacon State (e.g., more validators = higher

validator_pubkeyfootprint inBeaconState).Working memory isn’t designed to store large amounts of data—unlike disk storage—so investing in performant Solid State Drives (SSDs) becomes more necessary for Beacon nodes to stay in sync with peers. But SSDs aren’t cheap (compared to regular hard disk drives or HDDs), which bumps up the overhead of running a validator and reduces the incentive for participating in Ethereum’s consensus, especially for at-home stakers.

While we’ve seen different proposals to reduce the validator set size (e.g., validator set capping and validator set rotation), EIP-7251 is currently the only proposal that reduces validators without requiring massive changes to Ethereum’s technical infrastructure or staking economics. We can see how much gains implementing EIP-7251 can provide by using figures from five of the largest staking pools:

Lido: 290,000 validators (31.68%)

Coinbase: 137,000 validators (14.94%)

Figment: 38,000 validators (4.1%)

Binance: 33,000 validators (3.6%)

RocketPool: 27,000 validators (2.9%)

If each staking service in this list consolidated multiple validators into single validators with the maximum effective balance of 2048 ETH, the result would be:

Lido: 141 validators

Coinbase: 66 validators

Figment: 18 validators

Binance: 16 validators

RocketPool: 13 validators

Given that these staking pools combined control 525,000 validators, a mass consolidation will have a visible contracting effect on the total validator set as the previous calculations show. This is napkin math, as it assumes each validator has exactly 32 ETH, but it is still enough to show the real-world impact of validator consolidation on reducing the Beacon Chain’s validator set.

Moreover, it’s unlikely staking operators will immediately start running validators with effective balances in the region of 2048 ETH due to the increased slashing risk; a more realistic assumption is that staking pools will begin with smaller consolidations (e.g., combining 32 ETH validators to create a 64 ETH or 128 ETH validators). This is why distributed validator technology (DVT) needs to become battle-tested enough to be deployed in production staking environments; with DVT, large validators can be run on multiple machines to increase fault tolerance, enable faster recovery from downtime, and contain the effects of client bugs and machine failures to individual nodes.

Unlocking future upgrades

As explained in the introductory section, critical upgrades on Ethereum’s roadmap—most notably, single-slot finality (SSF) and enshrined proposer-builder separation (ePBS)—can only be implemented if the validator set reduces or at least remains within reasonable bounds (e.g., see Vitalik’s recent argument for sticking to 8192 signatures in a post-SSF world). EIP-7251 proposes a minimally disruptive solution for validator set contraction on Ethereum and effectively removes obstacles to activating single-slot finality, proposer-builder separation, and other upgrades that share “low validator set” as a dependency.

A slightly related benefit from EIP-7251 is reducing pressure to accelerate R&D efforts related to dealing with the challenges of an enormous validator set (most of which come with various second-order consequences, as past discussions have shown). This minimizes demand for more drastic changes like EIP-7514—which proposes to reduce the validator churn rate—in the future and ensures core developers can spend time working on other aspects of the protocol.

Making solo staking competitive

At first glance, EIP-7251 looks like an attempt to make life easier for large staking operators—but there’s more to the proposal to increase the maximum effective balance. For example, solo stakers also benefit from EIP-7251 due to the availability of compounding rewards and the opportunity to stake ETH in flexible sizes. Both features are crucial to make solo staking attractive and bolster economic decentralization on the Beacon Chain.

To put things into context: a solo staker with a single 32 ETH validator will have to accrue rewards for years before it earns the 32 ETH required to activate another validator. Conversely, a staking pool with multiple 32 ETH validators can activate a new validator in a shorter time by consolidating rewards from existing validators. This places the staking pool in an advantageous position as it can earn more rewards from the newly activated validator.

With EIP-7251, a solo validator that migrates to 0x02 credentials can re-stake rewards (not to be confused with EigenLayer’s restaking model) and earn higher rewards from having a higher effective balance. This mimics the compounding process adopted by staking pools, which I described earlier, and shows that adopting EIP-7251 is ideal for solo stakers as much as for large staking services.

Reducing operational overhead for large staking pools

A staking service operator today is running anywhere from 1,000 to 10,000 validators (or more) on a single machine, which can problematic from a logistics perspective. Since maximizing ROI on staked ETH is the primary reason for running many validators, EIP-7251 ensures staking pools can continue to run profitably with fewer validators by consolidating validator balances in protocol.

The ability to set variable ceilings for a validator’s maximum effective balance also reduces the necessity of activating new validators, as rewards can accrue and compound for more extended periods before the MAX_EFFECTIVE_BALANCE threshold and the automatic partial withdrawals sweep starts. A potential benefit is that node operators can manage fewer validator keys and scale down the complexity of signing key management.

Are there any drawbacks to implementing EIP-7251?

Increased slashing penalty risk for large validators

The slashing risk borne by validators with higher effective balances is arguably the biggest argument against implementing EIP-7251. Some might even argue that the risk of running a validator with a larger slashable balance outweighs the net benefit from consolidating validators, especially if the linear scaling properties of the initial penalty and correlation penalty remain unchanged.

Nonetheless, I’ll play devil’s advocate and propose some counterarguments:

EIP-7251 proposes modifications to slashing mechanics (e.g., changing the scaling properties of initial/correlation penalties) as described in the slashing penalty analysis document. If the various proposals are implemented, the risk profile for large validators is reduced significantly.